Blog

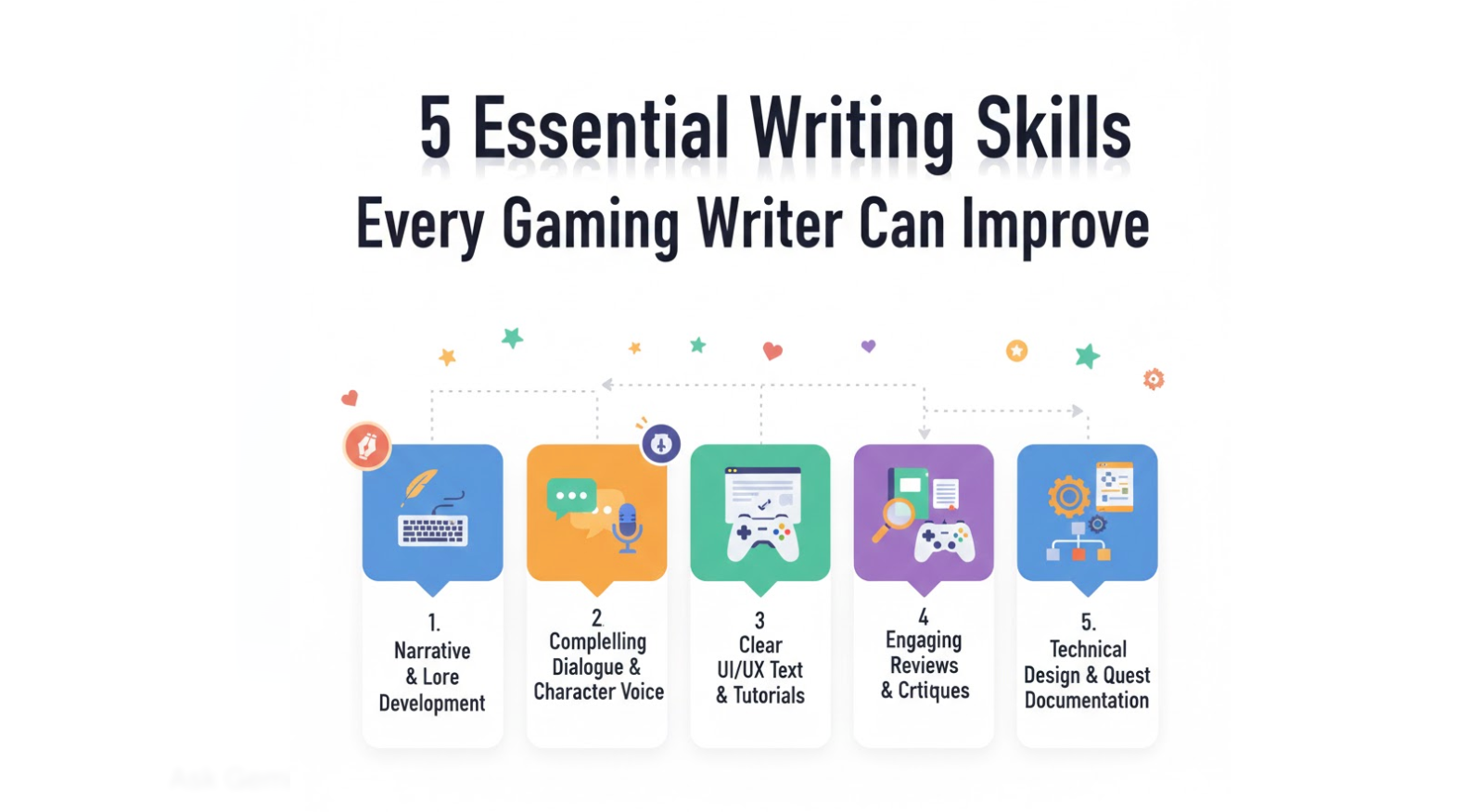

5 Essential Writing Skills Every Gaming Writer Can Improve

Gaming writing is one of the most misunderstood forms of content creation out there. A lot of people think it is just about playing games and then typing whatever comes to mind. But if you have spent any time trying to build an audience around gaming content, whether that is reviews, guides, lore breakdowns, or feature articles, you already know it is much harder than it looks. You are writing for readers who know their subject deeply, who can spot a factual error immediately, and who have extremely high expectations for quality.

The good news is that gaming writing, like any other skill, can be improved with the right focus and practice. There are specific areas where most gaming writers, including experienced ones, tend to fall short. And when you work on those areas deliberately, the quality of your content improves noticeably.

This article covers five core writing skills that gaming writers at every level can sharpen. These are not abstract writing tips you have heard a hundred times. They are practical, specific, and built around the real challenges that join gaming content presents. Whether you write for a personal blog, a YouTube channel, a major publication, or a game studio, these skills matter and they make a real difference.

Building a Recognizable Writing Voice That Readers Come Back For

One of the biggest problems in gaming writing today is that most content sounds the same. If you pick up ten different gaming review articles from ten different websites, there is a good chance you will struggle to tell them apart. They use the same structure, the same kinds of phrases, and the same approach to describing games. That kind of writing does not build an audience. Readers have no reason to come back to you specifically because they could get the same experience anywhere else.

A writing voice is not something you manufacture. It comes from how you actually think about games, what you notice that other people tend to miss, what bothers you, what excites you, and what you genuinely believe. The problem is that a lot of gaming writers suppress all of that in an attempt to sound professional or neutral. They end up writing in a flat, detached way that feels like it was written by nobody in particular.

Writing coach Roy Peter Clark, who has worked with journalists and feature writers for decades, has pointed out that readers form emotional connections not with topics but with the people writing about them. That holds true for gaming content just as much as it does for political commentary or personal essays. When readers feel like there is a real person behind the words, they keep coming back.

So how do you actually develop a voice? The first step is to stop filtering yourself so aggressively. If you find a game’s camera system genuinely irritating, say so directly. If a game’s story moved you in a way you did not expect, explain exactly why. If you think a widely praised game is overrated, make that case with specifics. Readers respond to specificity and conviction far more than they respond to carefully hedged, middle-of-the-road opinions.

The second step is to pay attention to the kinds of things you naturally gravitate toward when you are playing a game. Some writers notice sound design first. Others zero in on movement mechanics, or how a game handles difficulty, or what the loading screens look like. These natural tendencies are part of your voice. They are the angle from which you see games, and that angle is unique to you.

The third step is to read your own older work critically. Look for the places where you played it safe or used generic phrasing when something more specific would have worked better. Notice where you repeated words or ideas without meaning to. That kind of honest self-review helps you understand your current writing patterns and identify where your voice is getting diluted.

Here is a practical breakdown of habits that strengthen versus weaken your writing voice in gaming content:

| Writing Habit | Strengthens Voice | Weakens Voice |

|---|---|---|

| Describing gameplay | Uses a specific moment from the game | Describes mechanics in general terms |

| Giving opinions | States a clear view without over-qualifying | Hedges every claim with “some may feel” |

| Making comparisons | Uses personal, unexpected comparisons | Uses genre clichés like “Dark Souls-like” without further thought |

| Discussing story | Connects plot to personal reaction | Summarizes plot without any interpretation |

| Opening paragraphs | Starts with something specific and unexpected | Starts with “In the world of gaming…” |

A useful exercise is to take one paragraph from something you wrote recently and rewrite it three times, each time pushing your language slightly further toward your actual opinion. In the first version, stay close to what you originally wrote. In the second, make your opinion a bit more direct. In the third, remove all qualifications and write exactly what you think. Then compare all three. Most writers find that the third version, the one they were most afraid to publish, is actually the most interesting to read.

- Another thing worth understanding is that voice is not the same as personality.

- You do not have to be funny or aggressive or edgy to have a strong voice.

- You just have to be consistent and specific. A writer who always focuses on the emotional logic of game design decisions, explaining clearly why a particular design choice makes players feel a certain way, has a strong voice even if their tone is calm and analytical.

- The voice is in the angle, not the attitude.

Tips for developing your writing voice as a gaming writer:

Write one piece per month where you take a clear, strong position on something in gaming that most writers avoid having an opinion about. Keep a running list of phrases you use too often and replace them whenever they appear. After finishing a draft, read it aloud and notice where you sound like yourself and where you sound like everyone else. Study writers you admire not to copy them, but to understand specifically what they do that nobody else does. Write about games you have a complicated relationship with, not just ones you loved or hated, because that complexity tends to produce the most honest and interesting writing.

Writing Game Descriptions That Actually Help Readers Understand What a Game Feels Like

Most gaming writers underestimate how hard it is to describe a game well. It seems like it should be straightforward. You play the game, you watch what happens, you write about it. But good game description is genuinely difficult because you are trying to translate an interactive, multi-sensory experience into flat text. When you do it badly, the reader gets a list of features. When you do it well, the reader gets a real sense of what it feels like to play.

The feature-list problem is extremely common in gaming writing. A writer will say something like “the game features open-world exploration, crafting systems, and a dynamic weather engine.” That sentence is technically accurate but it tells the reader almost nothing about what the experience is actually like. Is the open world fun to move around in? Does the crafting feel meaningful or tedious? Does the weather affect gameplay in ways that matter? None of that comes through in a feature list.

Veteran games journalist Keith Stuart, who has written about games for The Guardian for many years, has argued that the best game descriptions work by finding the specific detail that carries the whole experience. Instead of describing every system in a game, you find the one moment or mechanic that captures the feeling of the entire thing, and you describe that with care. That approach tends to produce writing that readers actually remember.

Think about the difference between these two descriptions of the same game. The first version: “The game has a stealth system that lets you hide in shadows, distract enemies with thrown objects, and take them down quietly from behind.” The second version: “There is a moment early in the game where you are crouched behind a crate, watching a guard pace back and forth, and you realize you have been holding your breath for the last thirty seconds. That is what the stealth feels like.” The second version does not list features. It creates a feeling. And that feeling is what the reader needs to decide whether they want to play the game.

To write descriptions like that, you need to slow down while you are playing and pay attention to your own reactions. When did you lean forward? When did you get frustrated in a way that made you want to keep going rather than quit? When did you laugh or wince or feel genuinely surprised? Those reactions are the material you need. The game’s systems are just the context.

Here is a comparison of weak versus strong game description techniques:

| Description Type | Weak Example | Strong Example |

|---|---|---|

| Combat feel | “Combat is fast-paced and responsive” | “Every hit lands with a weight that makes you feel the difference between a glancing blow and a clean strike” |

| World design | “The open world is large and detailed” | “You can stand at the edge of a cliff and see the next three areas you are going to spend the next ten hours in” |

| Difficulty | “The game is challenging but fair” | “You will die on the same boss fifteen times and on the sixteenth attempt you will finally read what it is actually doing” |

| Story tone | “The story is dark and emotional” | “The game kills a character you have known for four hours and the writing is good enough that it actually hurts” |

| Pacing | “The game has good pacing” | “The slow sections feel slow on purpose, and the game earns its quiet moments by making the loud ones genuinely loud” |

One thing many gaming writers do not practice enough is describing games they did not enjoy. It is relatively easy to write enthusiastically about a game you loved. It is much harder to write clearly and fairly about a game that did not work for you. But the ability to describe why a game fails, specifically and without contempt, is one of the most valuable skills in gaming writing. Readers trust writers who can explain failure as clearly as they explain success.

Practical tips for improving how you describe games:

Play for at least an hour before you write a single word about how something feels, because your first impressions are often about your own adjustment period rather than the game itself. Write descriptions of games without using genre labels at first, because genre labels are shortcuts that stop you from seeing clearly. After writing a description, ask yourself whether someone who had never heard of the game could understand what it feels like from your words alone. Practice describing non-gaming experiences, like a meal, a piece of music, or a physical sensation, using only sensory and emotional language. Then apply that same approach to games.

Getting the Structure of a Gaming Article Right So Readers Stay Until the End

A lot of gaming writers put serious effort into their ideas and their research but then lose readers halfway through because the structure of the article is not working. Structure is not just about having an introduction, a middle, and an ending. It is about knowing what information readers need at each stage of reading and giving it to them at the right time.

The most common structural mistake in gaming writing is front-loading all the interesting material and then trailing off into less compelling territory. A writer will open with a strong hook, build momentum through the first few sections, and then spend the final third summarizing what they already said or covering details that should have been cut entirely. Readers feel that drop in energy and they stop reading.

The second most common structural mistake is burying the most interesting point. This happens when writers treat their best idea as a conclusion rather than as a foundation. If the most interesting thing you have to say about a game is that its failure to let players save manually is the single biggest design flaw in an otherwise excellent experience, that should not appear in your penultimate paragraph. It should be near the top, and everything else in the piece should build around it.

Writing researcher George Gopen, who studied how readers process sentences and paragraphs, found that readers consistently look for the main point in specific structural positions, and when the main point is not where they expect it, they miss it or misread it. This applies directly to gaming articles. If your key argument is buried in the middle of a long paragraph that is itself buried in the third section of a five-section piece, most readers will miss it.

Good structure in a gaming article means knowing your main argument before you start writing, not after. It means deciding which information is supporting material and which is the central claim. It means being willing to cut sections that are interesting but do not actually serve the piece. And it means ending in a way that gives the reader something to take away, not just a summary of what they just read.

Here is a structural guide for common types of gaming articles:

| Article Type | Opening | Middle Sections | Closing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Game review | The moment that defines the whole experience | Specific systems analyzed with examples | What kind of player this is and is not for |

| How-to guide | The problem the reader is trying to solve | Step-by-step with context for each step | What to do when the standard advice does not work |

| Opinion piece | The claim stated directly | Evidence and reasoning, then strongest counterargument | Why the claim still holds after the counterargument |

| Lore breakdown | The question that makes the lore interesting | Piece by piece evidence from the game | What the lore means for how we understand the game |

| Industry analysis | The trend or problem being examined | Data, examples, expert perspective | What this means for players and the future |

Another structural issue specific to gaming writing is how to handle spoilers. Many writers either avoid all spoilers so completely that they cannot make any real arguments, or they ignore spoiler concerns entirely and drive away readers who have not finished the game. The better approach is to signal clearly what is and is not spoiler territory, group spoiler content together rather than scattering it throughout the piece, and make sure that the non-spoiler sections of the article are valuable on their own.

Tips for improving article structure in gaming writing:

Write a one-sentence summary of your main argument before you write anything else, and check at the end whether the article actually delivers on that sentence. Use the first paragraph of each section to tell the reader what that section is going to argue, not just what topic it covers. Read your completed draft and mark every sentence that could be cut without losing any important information, then cut at least half of those sentences. Practice writing articles that make one point very well rather than ten points adequately. Read the endings of your articles separately from the rest and ask whether they give readers something new or just repeat what came before.

Doing Real Research for Gaming Content Instead of Recycling What Everyone Else Already Said

Gaming writing has a serious research problem. A large portion of gaming content online is built on the same small pool of information that gets passed from site to site. A writer reads three other articles about a game, synthesizes what those articles said, and publishes a new piece that adds very little. That cycle produces content that feels thin even when it is technically accurate, because the underlying information has been diluted through multiple rounds of paraphrasing.

Google’s Helpful Content Update was specifically designed to identify and reduce the visibility of this kind of content. The update prioritizes material that demonstrates genuine expertise and first-hand experience, and it penalizes content that exists primarily to capture search traffic without providing real value. For gaming writers, this means that recycling information from other gaming sites is not just ethically questionable, it is increasingly bad for your search visibility.

Real research for gaming content takes several forms. The most obvious is first-hand play experience, actually completing the game or spending significant time with it before writing about it. But research also includes reading developer interviews and postmortems, which are often full of specific details that never make it into mainstream coverage. It includes looking at how players in forums and communities are actually talking about a game, what problems they are running into, what they love about it that reviewers did not mention. It includes checking sales data, development timelines, and company history when those things are relevant to your argument.

Game designer Raph Koster, who has written extensively about game theory and design, has noted that most games criticism stays at the surface level of player experience without engaging with the design decisions that produced that experience. Getting closer to the design layer, understanding why a game was built the way it was, almost always produces more interesting and useful writing than staying purely in the player experience layer.

One underused research approach in gaming writing is direct comparison with historical games. When a new open-world game comes out, most reviews compare it to other recent open-world games. But comparing it to open-world games from ten or fifteen years ago often reveals more interesting things about how the genre has changed, what ideas have been lost, and what assumptions have calcified. That kind of historical perspective requires actual knowledge of older games, which takes time to build, but it is exactly the kind of knowledge that makes a gaming writer genuinely valuable rather than replaceable.

Here is a breakdown of research sources and how to use them effectively:

| Research Source | What It Gives You | How to Use It |

|---|---|---|

| Developer interviews | Design intentions and constraints | Compare stated intentions to actual player experience |

| Game credits | Who made what | Track creative teams across projects to understand patterns |

| Player forums and Reddit | Real player reactions and problems | Find the complaints that reviewers missed |

| Patch notes history | What was changed after launch | Understand how the game evolved and what the studio prioritized |

| Academic game studies | Theoretical frameworks | Apply academic ideas to make your criticism more rigorous |

| Speed run communities | Deep mechanical knowledge | Learn how the game’s systems actually work at a technical level |

| Developer postmortems | What went wrong and why | Write about production context that explains the final product |

Something worth understanding about research in gaming writing is that the goal is not to accumulate information for its own sake. The goal is to have something to say that you could not have said without doing the work. If your research does not change or deepen what you originally planned to write, you may not have done the right kind of research. Good research surprises you. It changes your opinion or complicates it. It gives you a piece of information that reframes everything else you thought you knew about a game or a studio or a genre.

Tips for improving your research process as a gaming writer:

Before writing anything, write down your initial opinion or hypothesis about what you are going to argue, then actively try to find information that contradicts it. Read at least one developer interview or postmortem before publishing anything that makes claims about a game’s design. Check your claims against primary sources rather than other gaming articles whenever possible. Keep notes while you play, because specific details you notice in the moment are much more useful than general impressions you try to reconstruct after the fact. Build a habit of reading about games you are not currently covering, because that background knowledge will show up as depth in your writing even when you cannot directly cite it.

Editing Your Own Gaming Writing Until It Actually Says What You Meant

Most gaming writers do not edit enough. There is a common belief that editing means fixing typos and correcting grammar, which is true but barely scratches the surface of what editing actually involves. Real editing means reading your work with enough distance to see what it actually says rather than what you intended it to say. It means cutting the sections that feel good to write but do not serve the reader. It means rewriting sentences until they are clear rather than just grammatically correct. And it means being honest with yourself about whether your argument actually holds up under scrutiny.

The distance problem is real. When you finish a draft, your brain remembers what you were trying to say, and it reads that into the text even when the text does not actually say it. This is why rereading your own work immediately after finishing it is so ineffective. You are essentially reading your own memory rather than the words on the page. The standard advice to wait before editing is genuinely useful, and twenty-four hours makes a meaningful difference. After a day away, you can read more honestly.

Author and editor Sol Stein, who worked with some of the most important writers of the twentieth century, made the distinction between an author reading for pleasure and an editor reading for problems. An author reads and feels satisfied when the writing flows. An editor reads and asks whether every sentence is doing necessary work, whether every section earns its place, and whether the reader’s experience at each moment of the piece is the intended one. Gaming writers need to develop the ability to switch into that editorial mode, even when reading their own work.

One specific editing skill that gaming writers rarely develop is cutting for length without cutting meaning. Most first drafts of gaming articles are too long, not because the writer has too many ideas but because ideas are expressed inefficiently. A sentence that takes thirty words to make a point can often make the same point in fifteen. A section that takes four paragraphs to set up an argument can often set it up in two. The material that gets cut in this process is not wrong, it is just not necessary, and its absence makes the remaining material stronger.

Another editing skill specific to gaming writing is checking claims about games against your actual experience. It is easy to write something like “the combat feels sluggish in the early hours but opens up later” and then, when you go back to edit, realize that you cannot actually remember whether that is true or whether you just read it somewhere else. That kind of claim needs to be verified, either by going back to the game or by being more honestly hedged in the writing.

Here is a checklist approach to editing gaming content at different levels:

| Editing Level | What to Check | Common Problems Found |

|---|---|---|

| Argument level | Does the article make a clear, defensible claim? | Pieces that describe without arguing anything |

| Structure level | Does each section follow logically from the last? | Sections that could be reordered without changing anything |

| Paragraph level | Does each paragraph make one clear point? | Paragraphs that mix two separate ideas |

| Sentence level | Is every sentence as clear and short as it can be? | Sentences with three clauses where one would do |

| Word level | Are there vague or overused words that should be replaced? | Words like “interesting,” “great,” “unique,” and “amazing” |

| Fact level | Are all claims about the game accurate and verifiable? | Claims based on memory rather than experience |

One editing habit that gaming writers should build is keeping a personal list of their most common writing problems. If you know that you tend to start paragraphs with “This,” or that you use the word “actually” too often, or that your introductions run three paragraphs longer than they need to, you can specifically look for those problems when you edit. That kind of targeted self-editing is far more effective than general proofreading.

The final stage of editing should always be reading the piece from the reader’s perspective rather than the writer’s perspective. Ask yourself whether the reader has everything they need at each point in the article. Ask whether your assumptions about the reader’s knowledge are correct. Ask whether you have explained anything that needed more explanation or belabored anything that needed less. And ask whether the ending gives the reader something to think about after they have finished reading.

Tips for improving your self-editing process as a gaming writer:

Always edit in a format different from the one you wrote in, because changing the visual appearance of the text helps you read it more objectively. Read every sentence individually and ask whether it would make sense to someone who had not read the sentence before it. Cut every sentence that begins with “As I mentioned earlier” or “To summarize,” because both are signs of structural problems. Print your article and edit on paper at least occasionally, because the physical act of marking text catches errors that screen reading misses. Ask one other person who does not play games to read your article and tell you where they got confused, because their confusion points are usually places where you assumed knowledge your readers may not have.

Putting It All Together as a Gaming Writer

These five skills, finding and strengthening your voice, writing descriptions that create feeling rather than list features, structuring your articles so readers stay engaged, doing real research rather than recycling existing coverage, and editing until your writing actually delivers what you intended, are not separate disciplines. They work together. A strong voice combined with weak research produces confident-sounding content that does not hold up. Real research combined with poor structure produces thorough but unreadable pieces. Good structure combined with weak descriptions produces articles that are easy to follow but leave no impression.

The writers who build real audiences in gaming writing are the ones who work on all of these areas consistently over time. They are not necessarily the most knowledgeable people about games. They are not always the fastest or the most prolific. But they are the ones who treat writing itself as a craft worth improving, not just a vehicle for sharing gaming opinions.

One honest thing worth saying is that improvement in these areas is slow and it is not linear. You will write pieces where your voice comes through clearly and pieces where it completely disappears. You will do thorough research for one article and realize you got lazy with the next one. You will edit one piece until it is genuinely tight and then publish another one that needed three more rounds. That is normal. The goal is not perfection on any individual piece. The goal is a general upward trend over time, where each month of work leaves you slightly better than the month before.

Gaming writing has an audience that genuinely wants good content. Players are hungry for writing that treats games seriously, that brings real thought and real knowledge to the subject, and that gives them something they could not get from a trailer or a press release. That audience is waiting. The writers who put in the work to actually improve their craft are the ones who will find it.

The key focus areas across all five skills and what consistent practice in each one produces over time:

| Skill Area | What You Practice | What You Build Over Time |

|---|---|---|

| Writing voice | Stating opinions directly, writing with specificity | An audience that follows you rather than your topic |

| Game description | Describing feeling rather than features | Reviews and guides that readers share and remember |

| Article structure | Organizing around a clear argument | Pieces that hold attention from start to finish |

| Research habits | Going to primary sources, doing first-hand work | A reputation for accuracy and genuine expertise |

| Self-editing | Cutting, clarifying, and checking claims | Writing that says exactly what you meant it to say |

The most practical thing you can do after reading this is pick one of these five areas and focus on it specifically for the next four weeks. Not all five at once. Just one. Write with that skill in your mind, review your work with that skill as the primary lens, and read other writers with an eye toward how they handle that specific challenge. After four weeks, move to another area. That kind of deliberate, focused practice is how skills actually develop rather than just getting talked about.

Gaming writing deserves more seriousness than it usually gets, from the industry, from readers, and from writers themselves. When you treat it as a real craft with real skills worth developing, the work gets better. And when the work gets better, everything else that matters, the audience, the credibility, the opportunities, tends to follow.

Gamepad Tester – Controllers Tester Free Platform

Complete guide to test your gaming controllers with our advanced online gamepad tester. Test all buttons, analog sticks, triggers, and vibration motors across 20+ controller types, works with USB and Bluetooth connections, no downloads required.